Missing people remembered

“I

am not untouched by missing people,” noted Harry Lafond of the Office of the

Treaty Commissioner, opening speaker for a Reconciliation themed night focused

around missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls. One of his cousins

disappeared in the 1950’s, last seen climbing aboard a train to go to Prince

Albert from Marcelin. Nobody has been able to say what happened to her in the

past 60 years. His best friend also went missing in 1975, and has never been

found.

“It’s

not something that goes away. It’s not something you can let go of.”

He

spoke of how people have been treated since the treaty-signings, where the

dream and vision of sharing the land in harmony and being related has been

thrown out of balance by greed, power, and money.

“Not

just the Indigenous people but the settlers as well — it has thrown everything

out of balance, and as soon as something is out of balance you experience

unwellness. Pain. Suffering. Behaviour that is intended to hurt. That lack of

balance is what we’ve inherited from the Indian Act, the Residential Schools

that took one sentence of the treaty and twisted it to suit the interests of

the more powerful,” he explained, adding that this means a lack of respect for

all people, and respect between genders. “Women had a very strong role to play

in the democracy.”

Related:

-

Iskwewuk E-Wichiwitochik marks 10 years of supporting, advocating for families of MMIW

-

Liberal government says extensive consultations will precede national inquiry into MMIW

-

RCMP releases 2015 review of MMIW cases; Indigenous women still over-represented

Lafond

suggested we must return to the grandmothers’ voices again, so that men can

embrace an Indigenous society where we complement each other, not dominate,

oppress, or abuse, so as to rebuild families and live out the real dream of the

treaties.

After

Lafond spoke, Patricia Whitebear, Darlene Okemaysim-Sicotte, and Myrna LaPlante

all shared stories as relatives of disappeared or murdered women.

“This

is my forever lifetime commitment, my call of action,” noted Whitebear. “It’s

to bring awareness to yet another injustice of Indigenous families. We all have

family albums. Just imagine your family with one person missing every holiday,

Christmas, that person is not there. No one should feel that pain.”

Okemaysim-Sicotte

tied the issue directly into the legacy of Indian Residential Schools.

“Suffering

from the IRS seeks to share the harsh reality and the links to colonization

including the IRS and social environments. Many women today continue to be

challenged by safety and survival.

Colonial policies have attacked culture, way of life, way of being.

Traditional roles were undermined along with the dispossession of traditional

territories and roles and responsibilities, leaving women out of decisions,”

she noted. “Genocidal policies are linked to the disappearance of hundreds of

women.”

LaPlante

spoke about the life and contributions of her Aunt Emily who went missing at

age 76 in 2007 and has yet to be found.

“Once

she went missing, it was total disbelief, how can someone go missing from their

safe rural home and just vanish?” asked LaPlante. “We need to honour these

memories of these people who are missing and murdered and we need to remember

the things that they have done, the contributions they have made during their

lifetime, whether it was long or short.”

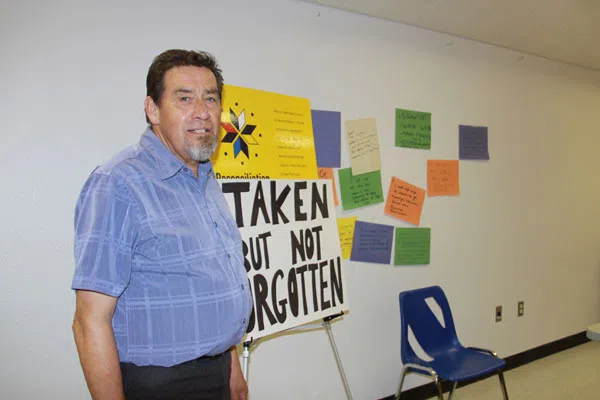

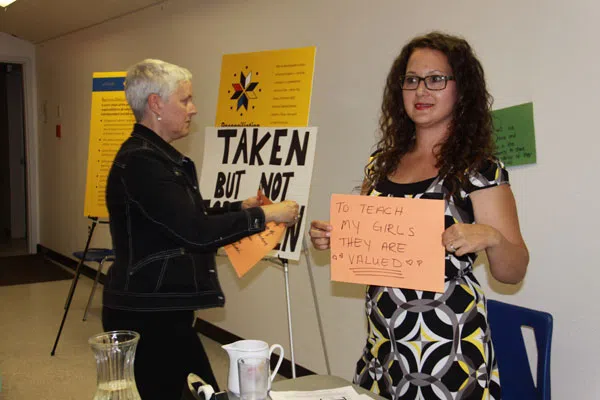

The

gathering then broke into small groups to discuss reconciliation, and make

resolutions on taking action, with opportunities to take “selfies” of their

resolutions next to the OTC Reconciliation posters, or the “Taken but not

Forgotten” poster board created by the organizers of the evening, Iskwewuk

E-Wichiwitochik. The evening ended with a round dance led by Joseph Naytowhow

and his sister Violet.