Exclusive Perspective Buffy: A Relative and Ally

The opinions shared are those of the author.

In 2012 I wrote the biography called Buffy Sainte-Marie: It’s My Way. My interests were both professional and personal.

As a university student in the 1970s, I had been greatly influenced by Buffy’s songs such as “Now That the Buffalo’s Gone,” which aroused awareness of Indigenous issues.

I knew of individuals that are mutual friends, and she claimed ties to the local Piapot First Nation.

I was searching for a research project.

No one had written her biography, and I was thrilled when she agreed to cooperate.

I conducted interviews and we exchanged several communications.

I did travel to Wakefield, Massachusetts as part of the effort to learn about her past. There I did hear the suggestion that she could have been born there.

So, I consulted with an expert in that state’s adoption practices and was told that at that time there existed a practice of creating birth certificates of convenience. It was believed that this would shield both adoptee and adoptive parents from unwanted questions.

That was satisfactory for me, as my intent in pursuing the biography was to tell Buffy’s inspiring story of her talent, activism and achievements.

The revelations about her birth record now present a challenge for all who have followed and appreciated her over six decades.

For myself, I think that Buffy truly felt that she had some sort of Indigenous roots.

Lenny Bayrd, a local well-known Indigenous crafts maker, influenced her as a child. Beyond that, it is difficult to assess any stories that Buffy’s mother may have told her, or why Buffy gravitated so strongly to an Indigenous identity when she left her home and began singing.

It is clear that early on Buffy was confused about her specific Indigenous identity.

But what impresses me is the passion and strength of Buffy’s attraction to Indigenous identity and causes.

In her defence, she grew up in the 1940s and 1950s when “the only good Indian was a dead one.”

I remember this from being in residential school in the 1950s and watching the then popular cowboy and Indian movies on television.

What we saw was a constant spectacle of our people being shot and killed – and all for the sake of entertainment! So, it was not a propitious time to identify as Indigenous. It took courage for Buffy to stand up the way she did. There was no guarantee that she would become rich in such a role, although her singing talent and visibility in the burgeoning Greenwich folk scene soon made her so.

The other thing about that era is that people were not so cognizant about issues of Indigenous identity, let alone cultural appropriation.

In Buffy’s generation, there were few Indigenous people in a position to attain the role she chose to fill. Her pioneering work in this area occurred in the context of working alongside existing Indigenous activists including the American Indian Movement.

To her credit, she contributed her public profile and financial resources, as well as put her personal safety on the line during protests from the 1978 Longest Walk to Washington DC, to occupation of Alcatraz, and standoff at Wounded Knee.

Her creation of initiatives such as the Nihewan Foundation and Cradleboard Project demonstrate that she was genuinely committed to improving Indigenous well-being.

Whatever her motives, one cannot deny the commitment and sacrifices Buffy has made.

It would have been far more lucrative if she had just stuck to singing and focussed on selling records. Being banned on radio at the behest of the White House over her protest songs shows how effective her influence was, as well as how her career was impeded.

After a hiatus, she did make a comeback. Her long-term success was based on Buffy’s raw talent.

For example, her 1982 Academy Award was not due to any Indigenous qualification. I do not believe that Buffy’s primary motivations were money and fame, but given her energy and talent, these things were inevitable.

Some may compare Buffy to Grey Owl.

I recall elder John Tootoosis, who met Grey Owl, saying that he said that he knew that Grey Owl was not authentic because he did not speak Cree nor did he place priority on ceremonies.

In Buffy’s case, her immersion in Cree culture, language, history and spirituality is laudable.

She has spent time learning from Elders and has engaged in ceremonies.

She understands our spiritual principles including values such as courage and generosity, and the value of positive relationships.

She invested the time to foster an impressive array of relationships, especially with her adopted family on Piapot, where she has maintained contact since the early 1960s.

Unfortunately, her choices have come at the expense of her relationships with the Sainte-Marie family.

Today, here is little excuse to masquerade one’s identity when it is now common knowledge how vital it is to take authentic Indigenous identity seriously.

So how are we to view Buffy now?

I have a new book coming out called Challenge to Civilization: Indigenous Wisdom and the Future.

I explore the role that Indigenous people need to play in the future.

I argue that returning to Indigenous ways and wisdom and its respect for the gifts of the Creator, is the only viable path for long term human survival.

One of the main points I make is that while it is essential that Indigenous peoples play the leading role, progress will not be possible without the help of non-Indigenous allies.

They hold much of the power and can change mainstream society from the inside.

Buffy has clearly been an ally, and an important one.

Could she have achieved as much without an Indigenous persona? I don’t know. But what she has achieved is important to recognize and respect as her actions have brought tangible benefits for us Indigenous folks.

Perhaps the term “Indigenous” needs to be more closely examined.

It is convenient that the colonial government of Canada has created a whole array of legal terms that define who is or isn’t considered to be Indigenous.

In my research, I have come to the conclusion that what is also critical in defining who could be considered “Indigenous,” apart from solely biology or belonging to a specific territory, is who adheres to Indigenous spiritual values – being stewards of the land, and living values such as courage, generosity and respectfulness.

The spokespersons for the Piapot family put it powerfully when they stated: “To us, that [traditional adoption] holds far more weight than any paper documentation or colonial record keeping ever could.”

Yes, facts are important. But can myth be even more powerful, especially when it is driven by passion and inner conviction?

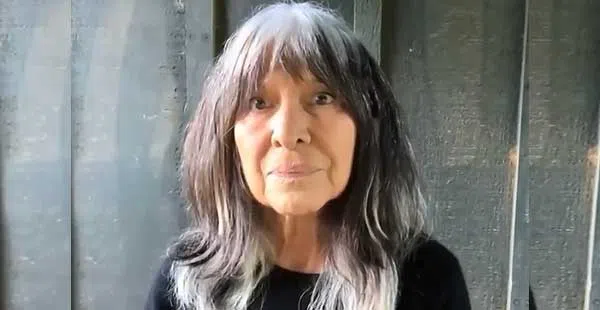

Blair Stonechild is a professor at the First Nations University of Canada since the1970s and has authored several books including Loyal Til Death, Pursuing the New Buffalo, The New Buffalo, Buffy Sainte-Marie: It’s My Way, The Knowledge Seeker and Loss of Indigenous Eden.